Anatomy Art

During the time of Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, art and anatomy were closely intertwined. Anatomy studies were mandatory for many art schools, and some artists were even writing anatomy textbooks for physicians. In the 16th and 17th centuries, anatomical depictions often portrayed the entire body in lifelike motion, while 18th-century anatomy atlases (especially on female anatomy) began to show figures in a more fragmented and detailed manner rather than as a whole. During this period of changing ideas about maternity, breastfeeding, and women’s responsibilities, highlighting sexual differences became crucial.

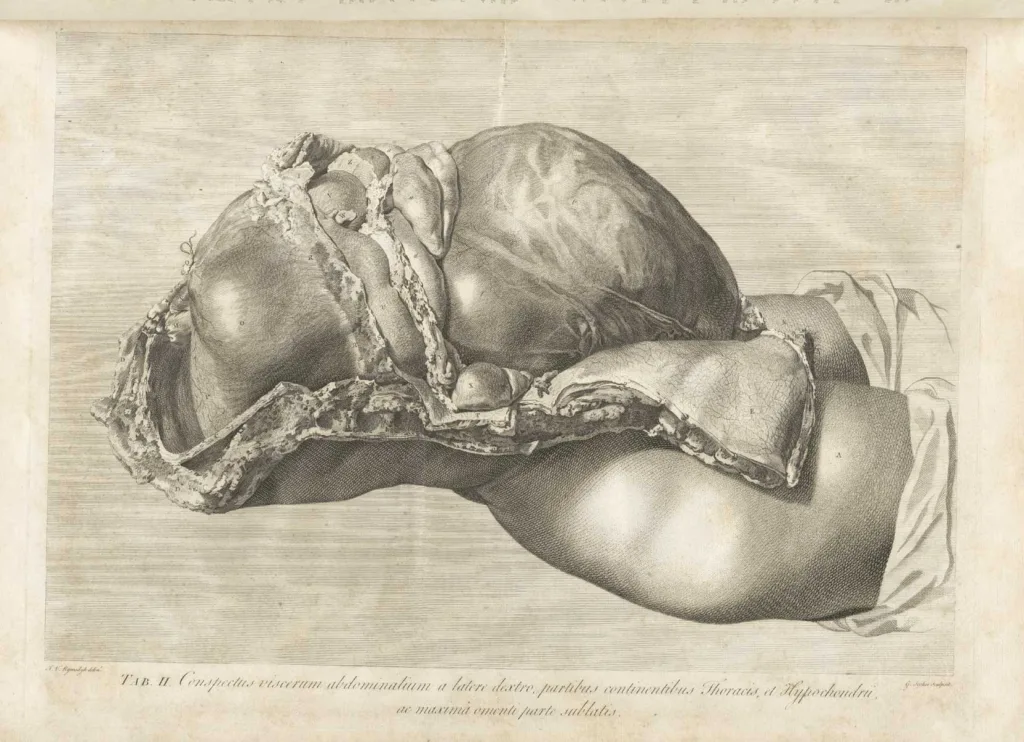

This era also witnessed the takeover of midwifery by men. The first male midwives (surgeons) like William Hunter and his colleagues needed to make female anatomy as transparent as possible to assist in childbirth. I had the chance to see William Hunter’s marvelous book, ‘Hunter’s Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus,’ at the Hunterian Museum in London. Published in 1774, the book stated that the drawings were done by skilled artists, but it did not mention the artist’s name. Intrigued, I delved deeper and discovered that 31 out of the 34 copper engravings in this extraordinary childbirth book were created by a mysterious figure named Jan Van Rymsdyk.

Van Rymsdyk (or Riemsdyk) was a Dutch artist living in England in the 18th century. Unfortunately, very little is known about him. Despite living in a time when people documented everything, there was scant information about the artist. Some historians speculate about his birthplace in the Netherlands around 1700-30, and he was presumed to have lived in England from 1745 to 1780, based on his style and influences. However, little else was known.

His small marginal notes provided clues about his life. He described a walk he took from The Hague to Scheveningen 36 years earlier (around 1742) and recounted a rainstorm in his garden after a severe drought in Jamaica. Although unverified, he might have lived in the Caribbean before moving to England.

Despite living in an age where everything was noted, he struggled to gain recognition as an artist. Some art historians speculate about his training based on his style, suggesting that he was born in Holland around 1700-30 and lived in England from 1745 to 1780, but little else is known.

His drawings and accompanying notes revealed glimpses of his life. In his notes, he mentioned the struggles of being denied the opportunity to develop as an artist. To earn a living, he painted portrait pictures, and it was through portrait painting that he was introduced to anatomical drawings. While creating portraits of local medical community members, including the midwife and surgeon Dr. William Barrett, he became acquainted with the medical community.

Although not earning enough, he found his way into anatomy drawings through portrait painting. The local medical community, including figures like Dr. William Barrett, commissioned him to create portraits. He was unhappy with his work on anatomical studies and blamed William Hunter, who he believed had discouraged him from becoming a “true” artist.

Van Rymsdyk was offered a job by William Hunter, who needed realistic depictions rather than “ideal” representations of the uterus in his upcoming book. Van Rymsdyk began working with John Hunter, William’s brother, dissecting corpses of women who died at various stages of pregnancy. Van Rymsdyk would create life-sized drawings with red chalk.

These drawings were almost photorealistic reproductions, showcasing even the smallest wrinkles and hairs. Other artists of the time criticized Van Rymsdyk for being too accurate and detailed in comparison to schematic drawings. Van Rymsdyk argued that there were three different ways to imitate an object: placing nature at an acceptable distance where all details are lost, portraying it from a closer distance where smaller parts become more visible (a distance other artists never surpassed), and drawing it from a distance where every minute point is explored. Van Rymsdyk had to use this last distance, which required him to get close to the object and discover every detail.

Despite his defense of his style, Van Rymsdyk was unhappy. He suffered. He secretly saw himself as inferior to “true” artists. He didn’t enjoy working on anatomical studies and accused William Hunter of mistreating him and turning him away from being a “true” artist. The painter might have been right; William Hunter did not mention Van Rymsdyk in his book but only referred to “skilled artists” in the preface. Clearly, Hunter believed that true art lay in dissection (surgical cutting).

There is no information about when or how Van Rymsdyk died, and the last record about him is a note from the editor of the third edition of Thomas Denman’s ‘Introduction to the Practice of Midwifery,’ published in 1791, referencing the ‘late author’ of the original volume. It is presumed that Van Rymsdyk died between 1788 and 1790.

Regardless of how Van Rymsdyk felt, he will always be remembered as one of the greatest medical illustrators of all time. He certainly did not sacrifice his talents; he used them for a greater good, contributing to the advancement of medicine.